Methane in the Arctic

This is a summary of work published in River Inflow Dominates Methane Emissions in an Arctic Coastal System, Geophysical Research Letters, 2020 and also discussed in my SM thesis.

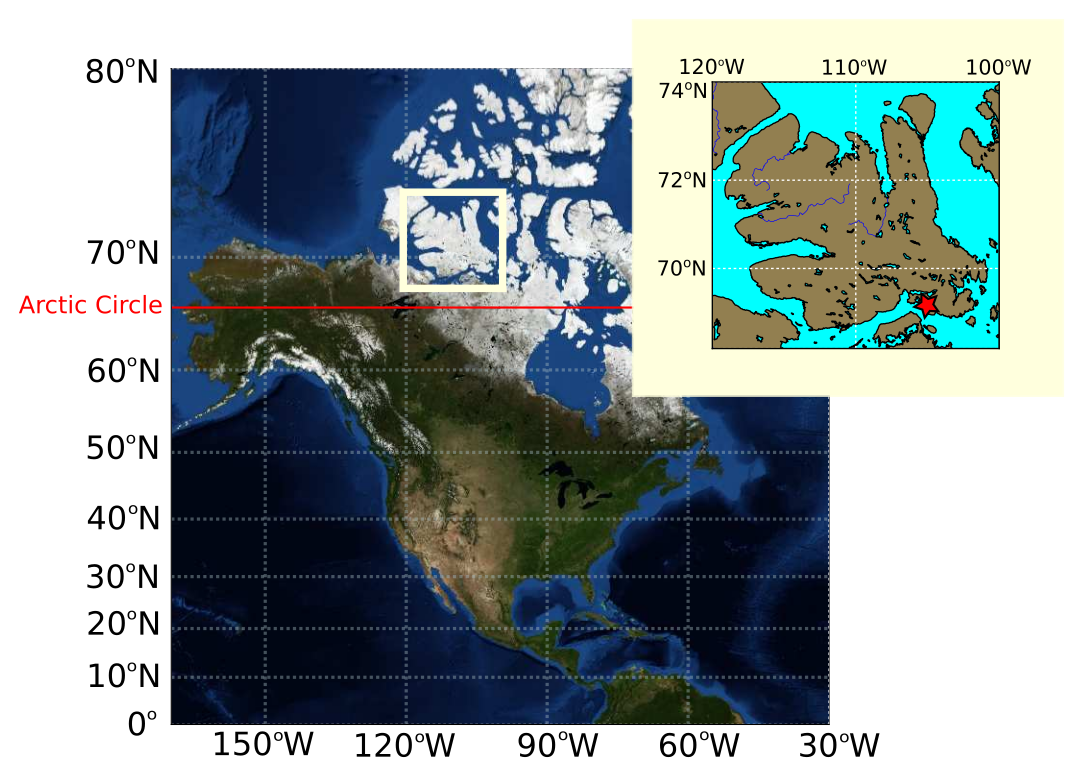

The Canadian High Arctic Research Station (CHARS) is located in Cambridge Bay (Iqaluktuuttiaq), Nunavut, Canada and can support a myriad of science parties with Arctic research based in the small town located on the southeastern coast of Victoria island. In early summer of 2018, I traveled with colleagues from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and University of British Columbia (UBC) to witness the transition of ice-covered to ice-free season on the river and estuary system co-located with CHARS. There, we performed dense spatiotemporal mapping of dissolved gases in Freshwater Creek, the Eastern arm of the Bay, over the course of several days.

Of particular interest to us was the dissolved concentration of methane in the estuary. The impetus for us traveling to Cambridge Bay was a year-long study conducted by UBC and collaborators in Cambridge Bay observing methane and other biogeochemical quantities from periodic water samples collected throughout a year. What these samples revealed was a seasonal bump of methane that built up under the ice-cover just at the beginning of the spring freshet, and receded following the break-up of the ice-cover for the summer. Seasonal variations in ice-cover are not uncommon in the Arctic, with many coastal areas experiencing both "ice-free" and "ice-covered" periods of the year. Despite this, the majority of gas flux studies performed in Arctic marine environments are conducted during the "ice-free" season. What UBC and collaborators discovered in their year-long study was that seasonal variations with respect to gas emissions may be considerable; and that the ice-free season may not provide an accurate representation of the Arctic contribution of greenhouse gases relevant for climate modeling, carbon-cycling computations, and nutrient transport studies.

Deployment in 2018 Field Campagin

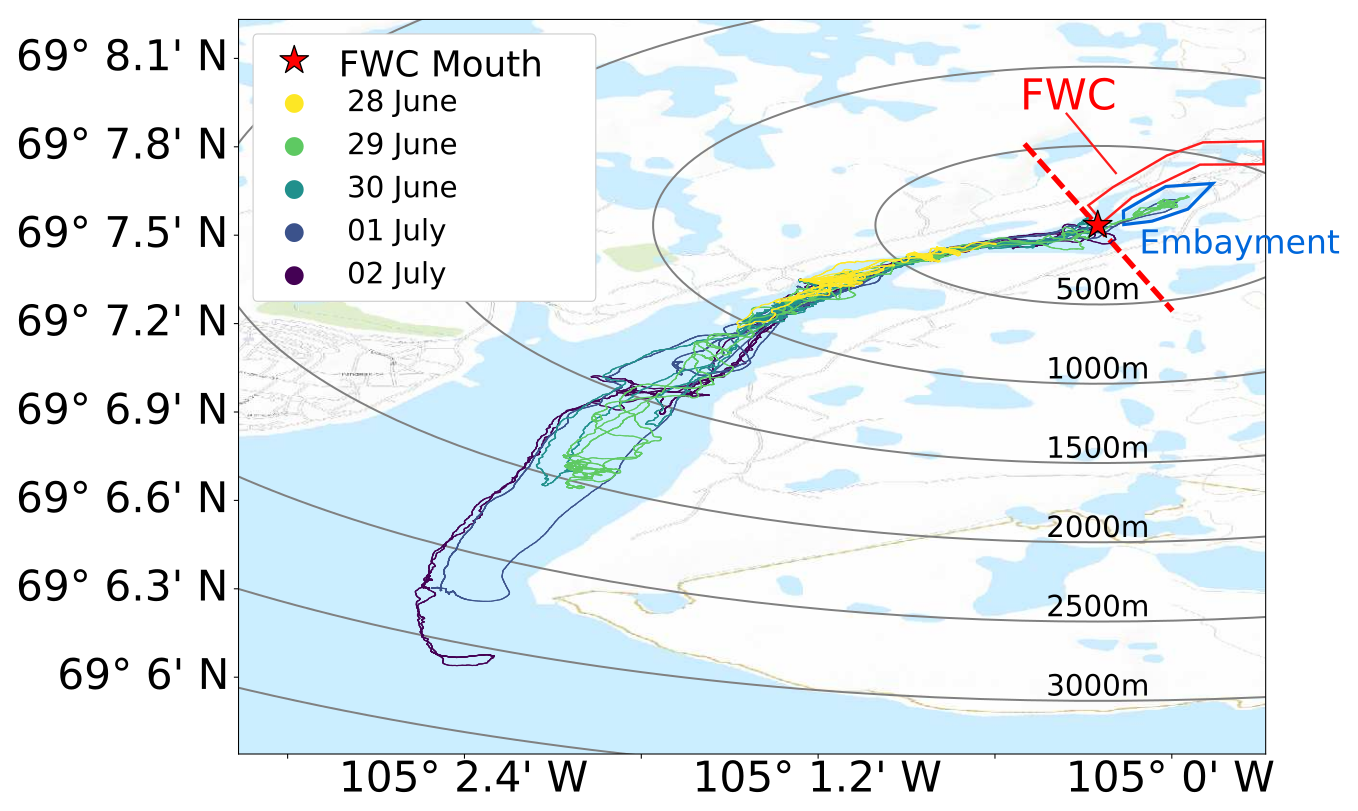

To better constrain the potential gas-flux that occurs over the short spring freshet period, we deployed a ChemYak in the ice-free regions of Freshwater Creek, and collected many thousands of observations of dissolved methane from June 28th to July 2nd with its onboard equipment. ChemYak is a retrofitted motorized kayak (a product familiar with some fishermen) with onboard weather station, dissolved gas extraction unit, gas analyzer, conductivity-temperature-depth (CTD) probe and winch, optode, and nitrate sensor. ChemYak is fully remote, and has rudimentary autonomous behaviors it can execute (under sufficient satellite coverage for GPS, a problem in the High Arctic).

Alongside a small "chase boat" which we rode in and collected physical samples for later ex situ analysis in a lab, we drove the ChemYak up to the receding ice age in the Bay, and then as far up Freshwater Creek as possible with the vehicle and back, drawing many long tracklines each day, pushing further into the Bay as the ice melted. The intent of these tracklines was to capture any spatial gradient that may be evident between the ice edge and the top of Freshwater Creek. With the onboard winch, we also raised and lowered the gas instrument inlet as well as CTD, meaning that we could additionally capture any vertical variation in gas distribution.

To inform each mission of the campaign, all observations taken by the ChemYak were downloaded at the end of a sampling day (8-10 hours) and processed, specifically looking at top-down spatial variations on a map, vertical spatial variations with probe depth changes, and daily temporal trends. While we elected to continue performing tracklines throughout the deployment, we added occasional intential vertical profiles, particularly near the ice edge, and spent a field campaign day traveling to Grenier Lake, the main inland water source for Freshwater Creek, via all-terrain vehicles (ATVs). For this particular field mission, we essentially took the "guts" from the ChemYak and secured them on our vehicles, then performed measurements from shore.

Observations from 2018 Field Campaign and Scientific Implications

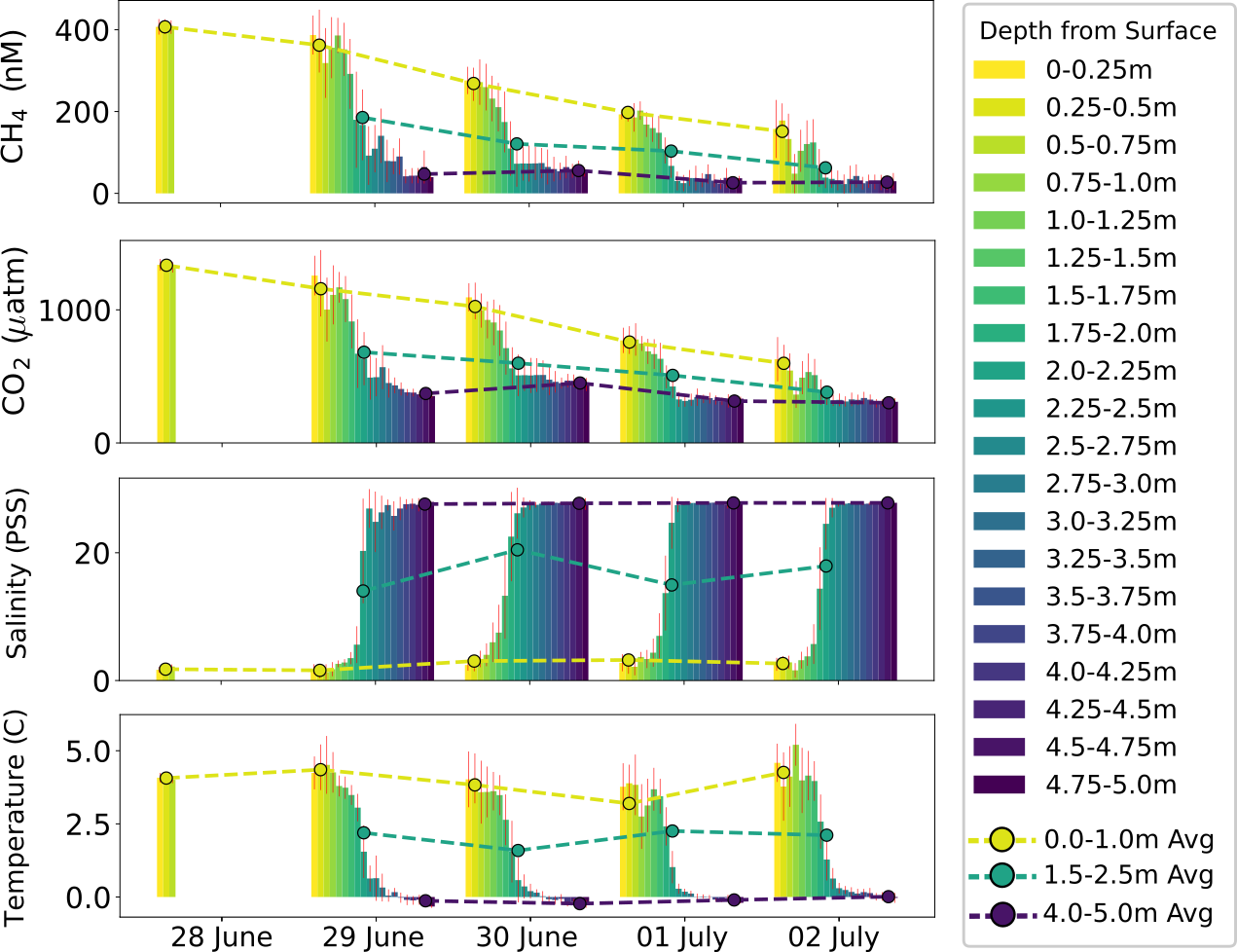

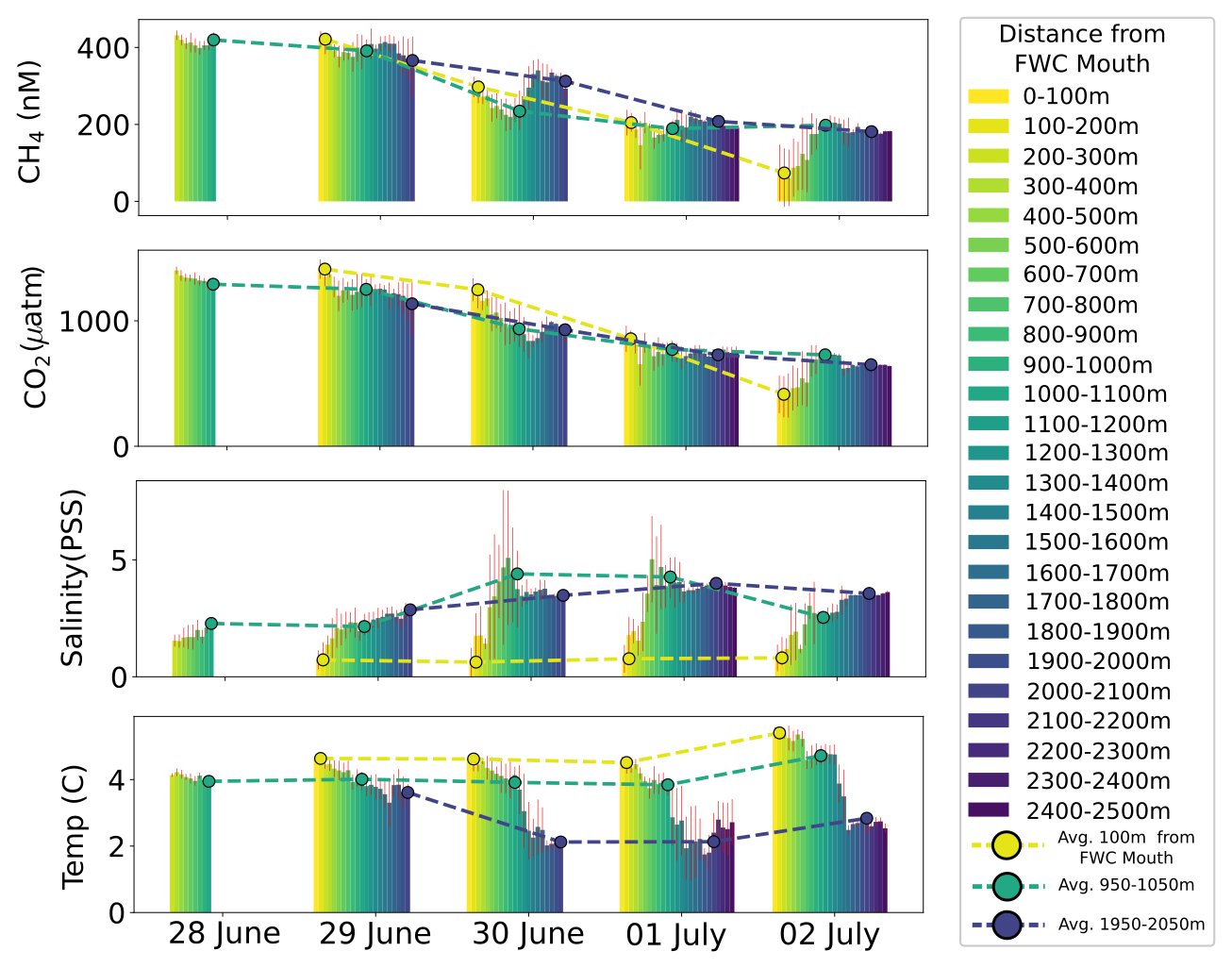

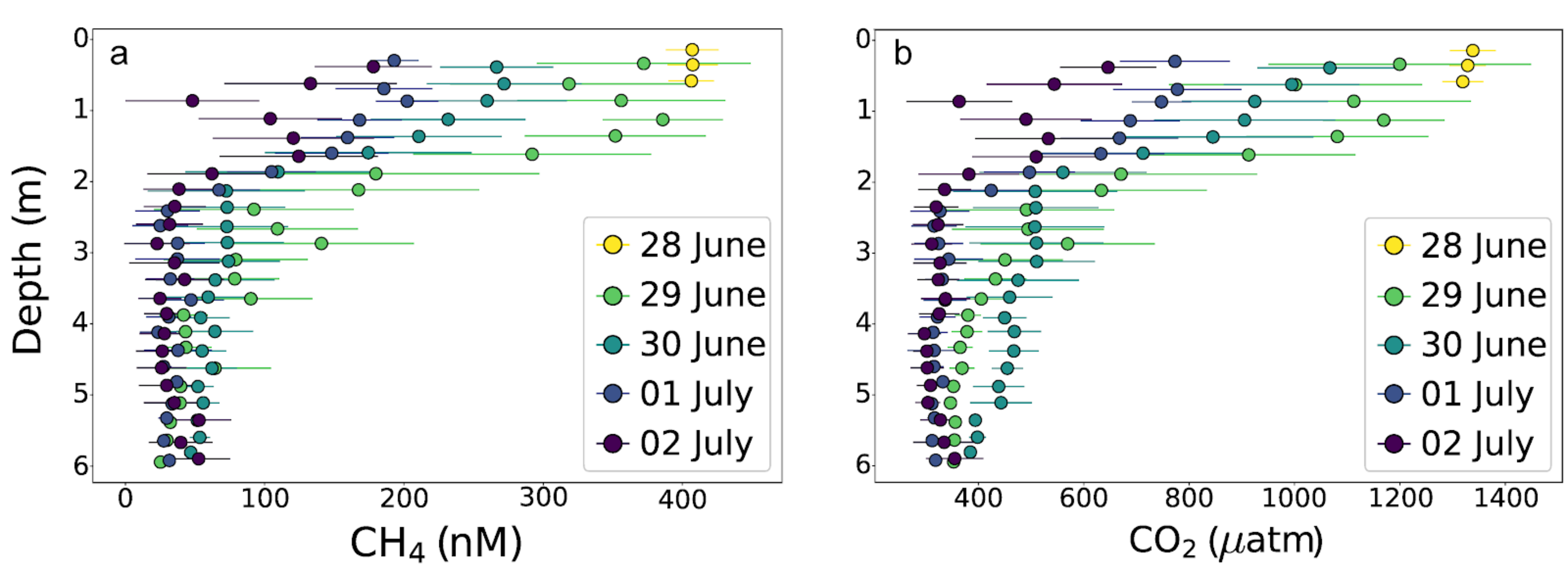

With the ChemYak, we observed a highly stratified water body with a warm, fresh, methane-rich lens in the top 2.5meters of the river persisting to the ice edge, and a salty, cold, and gas-poor under layer. Over the course of a 5 day stretch of the campaign, the average surface methane measurement of methane fell from an initial observation of ~400nM to near 200nM, with some evidence for mixing in the stratified layers shown by a less well-defined boundary layer over time. As a point of reference, for the temperature and salinity of the water sampled, an equilibrium concentration of merely 4nM would be expected.

These observations, coupled with completed ex situ analysis of bottles collected during the field campaign, and complemented with the long-term annual observations collected, paint a picture of a significant ephemeral out-gassing event in this coastal Arctic site. Using a simplified mixed layer model (that is, a physical mixing model that ignores biological or other external effects) of gas transport in the estuary and seeded with the observations taken, we estimate that more than 95% of all annual methane emissions from the estuary are driven by river inflow.

If we were to assume that all seasonally ice-free Arctic coastal environments have similar significant out-gassing events, then climate models which only consider summertime, ice-free measurements are ignoring the bulk of all greenhouse gas emissions from the Arctic. Disregarding the potential scale of this phenomenon, even if this were the only Arctic environment demonstrating this type of intense outgassing, it leaves questions about what drives this event: where is the methane coming from? Are there inter-annual changes? What proportion of methane mixes into the ocean versus escapes into the atmosphere? Understanding the carbon cycle in this type of environment would make it possible to better extrapolate what similar environments may exist in the Arctic, and whether the positive feedback cycle of climate change, which disproportionately impacts the Arctic, has a measureable effect on the phenomena.

Robots as Mobile Geochemical Observatories

The use of the ChemYak in this deployment demonstrated the utility of robots for geochemical monitoring. While we had a chase boat available, it could be easily imagined that the ChemYak could be operated from the shore, or semi-autonomously with planned or adaptive technologies. The ability for the ChemYak to get near the ice edge and other potentially hazardous locations without risk to human field operators provides a significant logistical advantage, and provides valuable access to otherwise risky measurement sites.

Robots like ChemYak represent a new paradigm for scientific work in natural environments. The ability to take many thousands of observations with non-trivial spatial and temporal coverage is a relatively recent innovation, where the previous state-of-the-art required direct human interaction and strong reliance on ex situ analysis, meaning significantly fewer observations a seldom real-time information. This opens the door to innovating the scientific method more generally while out in the field by way of adaptive or just-in-time planning, or potentially developing self-sustaining robotic observatories for in situ observation collection in lieu of persistent field campaigns or fixed observatories. Robots are particularly attractive because of their ability to study meso-scale environments --- satellites have revolutionized planetary and regional analyses, but are not spatially and temporally well-resolved; bottle samples are extremely sparse but are exacting and can be used to study arbitrarily small scales. The "middle ground" then, I argue, is where robots should be leveraged as scientific tools.

This campaign also highlights some of the remaining challenges that ushering a robot-centric future faces in the sciences, particularly in the Arctic. Satellite coverage (i.e., GPS coverage) is exceedingly limited in the Arctic and other remote environments. Cambridge Bay is also near true magnetic north, which can impact the realiability of compasses. Coupled, this makes navigation in the Arctic (aerially or terrestrially) challenging. During the spring freshet and ice-melt, large floating pieces of ice are not uncommon to observe, and are generally trecherous to be near (even for a robotic vehicle, the loss of which would be the end of a sampling campaign). And finally, embedding scientific questions or hypotheses into algorithmic behaviors is a general challenge which has implications for the levels of "intelligence" a robotic platform can possess, and thus it's utility as an independent agent. As a roboticist, these challenges can be used to motivate further innovations in localization, motion planning, scientifically-informed modeling and heuristics, and constrained decision-making.

Looking Ahead

Further field campaigns in Cambridge Bay were planned for summers 2020 and 2021, however due to the Covid-19 pandemic, these campaigns were postponed, with tentative plans to return in summer 2022. The focus of the next field campaign will be in tackling the question of where the methane is coming from (e.g., permafrost, biological decay, etc.) and further analysis of methane transport under retreating ice cover. This will be accomplished by deploying a novel sensor system which performs isotopic analysis of chemical targets (allowing us to effectively "date" the methane), and using the ChemYak in addition to a BlueROV underwater vehicle, and an aerial drone for image-based monitoring to complete the fleet.